A "Romantic" Digression

- sulla80

- Dec 31

- 6 min read

The New Year’s kiss is one of the most famous holiday traditions around. It can be a sweet way to ring in the new year with a partner, the slightly awkward result of too many glasses of Champagne, or the thrilling start of a new romance.

- The New Year’s Eve Kiss Tradition, Explained, by Gia Yetikyel and Anna Grace Lee, December 27, 2025

For the link between the New Year's kiss and Roman Saturnalia - see the article referenced above from Vogue. For today we will focus on "What are the origins of the modern English word 'romantic'?" and "How does this intersect with ancient Rome?"

Over the last 1,500 years, a word that started as a technical term for language, became a label for dragons and knights, evolved into a description of landscapes, and finally settled into a modern association with love.

We will explore the chronological evolution of the word.

The "Roman" Root (c. 5th–9th Century)

The origin is indeed the city of Rome. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Latin split into two forms: the formal Latin used by the Church/scholars, and the "vulgar" (common) dialects spoken by the people in France, Spain, and Italy.

To distinguish their everyday speech from formal Latin, people described their dialects as "Roman" (meaning "in the Roman manner" or "in the vernacular").

This is why French, Spanish, and Italian are still called the "Romance languages" today.

Examples:

"Visum est unanimitati nostrae, ut quilibet episcopus habeat omelias continentes necessarias ammonitiones, quibus subiecti erudiantur, id est de fide catholica, prout capere possint, de perpetua retributione bonorum et aeterna damnatione malorum, de resurrectione quoque futura et ultimo iudicio et quibus operibus possit promereri beata vita quibusve excludi. Et ut easdem omelias quisque aperte transferre studeat in rusticam Romanam linguam aut Thiotiscam, quo facilius cuncti possint intellegere quae dicuntur."

""It has seemed good to our unanimity that every bishop should have homilies containing necessary admonitions by which subjects may be educated—that is, regarding the catholic faith, insofar as they can grasp it; regarding the perpetual retribution of the good and the eternal damnation of the wicked; regarding the future resurrection and the last judgment; and regarding by which works blessed life may be merited or lost. And that each one should strive to translate the same homilies clearly into the rustic Roman tongue or the German tongue, so that all might more easily understand what is being said."

Source Text: Canon 17 from the Council of Tours (813)"Donc, le 16 des calendes de mars, Louis et Charles se réunirent en la cité qui jadis s'appelait Aygentariaÿ, mais burg' vulgo dicitur, convenerunt et sacramenta que subter notata sunt, Lodhuvicus romana, Karolus vero teudisca lingua?, juraverunt."

"Therefore, on the 16th of the calends of March [February 14th], Louis and Charles met in the city that was formerly called Argentaria, but is commonly called [Strasbourg]; they assembled, and the oaths which are noted below, Louis swore in the Romance tongue, but Charles in the German tongue."

Source Text: Historiarum Libri IV by Nithard (written c. 842-843 AD).From "Language" to "Stories" (Medieval Period)

Because "serious" books (science, theology) were written in Latin, the vernacular "Romance" languages were used for popular entertainment.

In Old French, a story written in the vernacular was called a "romanz" (or roman).

These stories were typically heroic tales of chivalry, magic, and courtly love (e.g., King Arthur).

Eventually, the noun "romance" stopped referring to the language and started referring to that specific genre of storytelling: tales of knights, adventure, and fantasy.

Examples:

Roman d'Alexandre (c. 1100): "The Tale of Alexander the Great."

Roman de Rou (c. 1160): "The History of Rollo" (a Viking duke).

Roman de la Rose (c. 1230): Literally "The Story of the Rose."

The Birth of "Romantic" (17th Century)

In the mid-1600s, English speakers coined the adjective "romantic" to describe things that were like those old medieval tales.

Initially, it was often used as an insult. To call something "romantic" meant it was "fictitious," "fabulous," or "unrealistic" - like a fairy tale.

If a person had "romantic ideas," it meant they were delusional or impractical, living in a fantasy world rather than reality.

Examples: This novel is a satire of a girl who reads too many romances and consequently has "romantic expectations" of reality.

"All the horrors: of her imagination were now wound up to the highest pitch. She recollected the dreadful adventures that she had read in her romances, and every image that presented itself to her view appeared a knight in armour, come to carry her off to-some inchanted castle."

-Charlotte Lennox, Entertaining history of the female Quixote, or the adventures of Arabella.and this dictionary entry:

18th Century Landscapes

In the 1700s, the word's meaning expanded to describe landscapes.

Travelers used "romantic" to describe wild, untamed places: ruins, jagged mountains, or deep forests, that looked like the setting of a medieval romance story.

A "romantic view" in 1750 did not mean a candlelit dinner; it meant a dramatic, awe-inspiring, or slightly spooky landscape that provoked deep emotion.

Example:

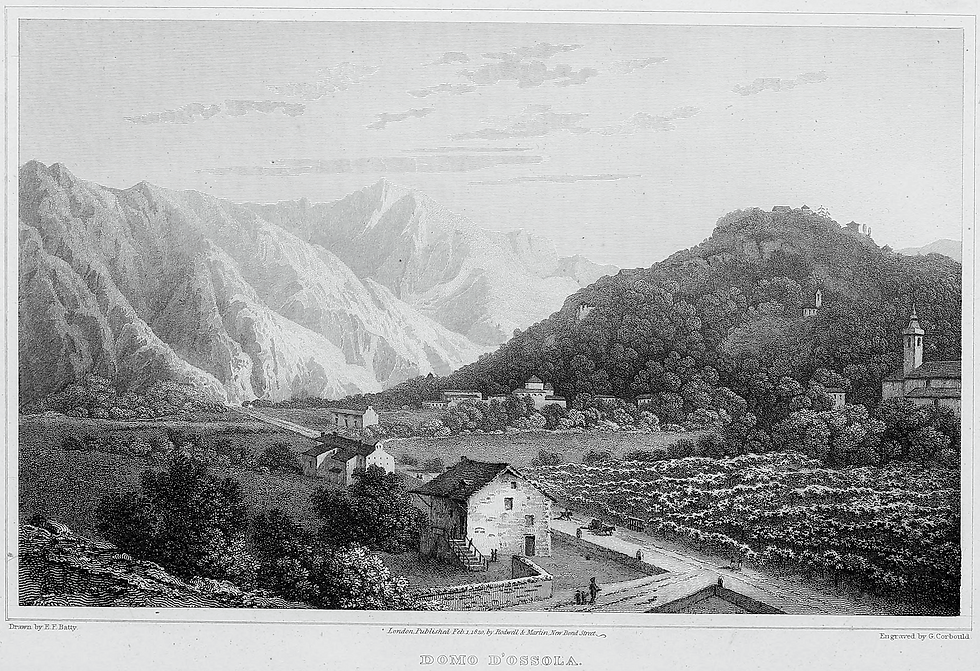

"Our regret at quitting the delightful scenery of the Lago Maggiore is compensated by the sublime and romantic beauties which unfold their wonders at every turn of the road. The whole way from the lake to Domo D'Ossola displays a succession of picturesque points of view, increasing in grandeur as we proceed farther towards the centre of this mountainous region."

-Elizabeth Batty, Drawings Made in 1817, published 1820The "Romantic" Movement (Late 18th Century)

German critics (like the Schlegel brothers) and English poets adopted the word to define a new artistic era: Romanticism.

They used "Romantic" to contrast their work with the "Classic." While "Classic" art emphasized order, logic, and ancient Greek rules, "Romantic" art emphasized emotion, nature, and imagination.

This movement rehabilitated the word, turning it from an insult (meaning "unrealistic") into a compliment (meaning "imaginative" and "deeply felt")

Examples:

"we conceive ourselves equally warranted in establishing the same division in dramatic literature, it might be sufficient merely to have stated this contrast between the ancient, or classical, and the romantic."

- August Wilhelm Schlegel, A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature the original German from 1808

The Romantic movement was viewed by later Modernists as melodramatic, mushy, sentimental, and undisciplined. They advocated for hard science and intellect in art. Piet Mondriaan illustrates the extreme opposite of Romantic in painting.

We can imagine a Romantic (in the spirit of this period of Art) version of my Roman republican coin:

The Modern Meaning (Love)

The specific association with love affairs is the most recent development.

While the original medieval romances did feature "courtly love," the word "romantic" primarily meant "adventurous" or "idealistic" for centuries.

It was only in the late 19th and 20th centuries that the definition narrowed to focus almost exclusively on intimacy and courtship, eventually leading to our modern concept of a "romantic dinner" or "romantic comedy".

The way most passionately sought in reaching for happiness is love - or, more accurately expressed, romantic love. (I regret that I did not add this important adjective frequently enough in the discussion of the psychology of love in this book.) In romantic love, the subject is certainly lost. The self scarcely exists. It is absorbed in the loved object.

-Theodor Reik, 1941, Of Love And Lust On The Psychoanalysis Of Romantic And Sexual Emotions

Best Wishes for a Joyful 2026

Comments