Exploring the AR Tetradrachm of Kyme: A Glimpse into Ancient Aeolis

- sulla80

- Jul 19, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 17, 2025

This map (a detail from The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1923) illustrates the western edge of Asia Minor, also known as Anatolia or modern Türkiye, during the Greek and Roman periods. I've highlighted Kyme (Cyme) on the map. There are other ancient cities named "Kyme," one near Naples in Italy and another on the island of Euboea.

In May of 2022, I wrote: "Eventually, I may give in and pay the price for an AR Tetradrachm of Aeolis, Kyme. So far, I haven't been able to convince myself that the price point is acceptable." That day has arrived. I am updating my 2022 notes on Amazon coins of Kyme and adding the AR Tetradrachm to the large AE, a civic issue from the city of Kyme in Aiolis.

The AR Tetradrachm from Kyme

The technical quality of this coin is impressive. It features a well-centered image with relatively fresh dies. The coin is evenly toned and well-preserved on a flan that is on the heavier end of the slightly reduced Attic standard, weighing around 16.5–16.8g.

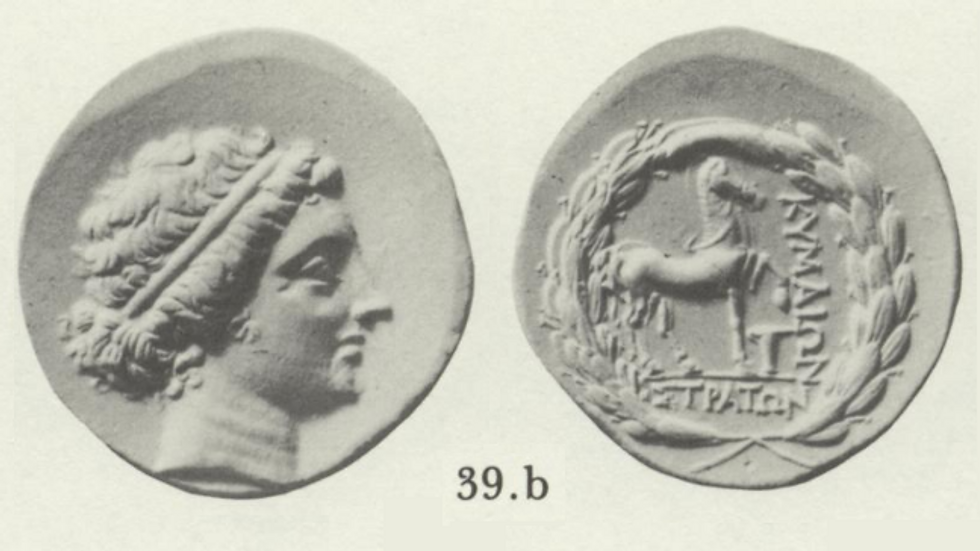

Greek, Aeolis, Kyme. AR Tetradrachm (Stephanophoric, 16.80g), Magistrate Straton, ca. 151/150–143/142 BCE.

Obv: Diademed head of the Amazon Kyme facing right.

Rev: Inscription KYMAIΩN with ΣTPATΩN in exergue; horse with bridle standing right, a one-handled vessel in front; all within a laurel wreath.

Ref: SNG von Aulock 1638-1639, SNG Cop 103-105 var. (Magistrate).

39b from Plate 7 of Oakley's 1982 die study appears to be the same obverse die.

There are five obverse die matches in ACSearch, with a couple like this one from Freeman & Sear that are double die matches to my coin. This is particularly evident on this coin due to the small obverse die break left at the base of the neck and the reverse position of the horse's hoof over the one-handled cup, commonly identified as a kantharos or wine jug.

The AE Coin from Kyme

The large AE version is a fine alternative and is harder to find in nice condition than the tetradrachm. This particular example has better imagery and a noticeably heavier flan than most others of this type in ACSearch. You can compare about 20 similar coins in ACSearch here with Pythas as magistrate

Greek: Aiolis, Kyme, Civic Issue Æ (21.5mm, 10.93g, 6h), circa 250-190 BCE, Pythas, magistrate.

Obv: Diademed head of Amazon Kyme to right.

Rev: Horse stepping to right, one-handled cup to lower right below raised foreleg; KYMAIΩΝ above, ΠΥΘΑΣ below.

Ref: SNG von Aulock 1635; SNG Copenhagen 102.

Understanding the Obverse Imagery

The Amazon Kyme depicted on the obverse is the mythical founder of the city. This representation celebrates its origins and honors a local legend on its coinage. The obverse references the myth of the founding of the city by the Amazon Kyme.

The Amazons were a fierce tribe of female warriors, known for their archery and horse riding. They fought against the Greeks. Myrina was a queen, and Kyme was one of her generals. Diodorus Siculus describes that Myrina named other cities after "the women who held the most important commands, such as Cymê, Pitana, and Prienê."

Encircling the design is a laurel wreath (stephanos), which gives these coins their name “stephanophoric” (wreath-bearing) tetradrachms.

There are many supposed etymologies for the name Amazon. One of the most commonly shared is the origin from ἀ and μαζός, a form of μαστός ("breast"), meaning "without a breast." This connection often relates to archers. The story may stem from this word-similarity, similar to other imagined etymologies. For instance, it was said that the Amazons did not know grain and were only meat and fruit-eaters, hence ἀ μάζα (without cereal food).

A more recent interpretation suggests that the Amazon myths are based on Scythian women who were Ἀμάξοίκος (wagon-dwellers). See Kazmer Ujvarosy (2016).

Herodotus tells a story of the Amazons and the Sauromatae or Sarmatians, an Iranian people in western Scythia, which is now modern Ukraine.

The Reverse Imagery

On the reverse, the prancing horse serves as a long-held civic emblem of Kyme (Cyme). In front of the horse’s forelegs is a small one-handled cup, commonly identified as a kantharos (wine jug). This likely alludes to the cult of Dionysos. The kantharos was used in Dionysian rituals, hinting that the worship of the wine god was significant in the city.

The reverse of this coin (the prancing horse) has several proposed explanations:

A connection to the cavalry training of the Amazons or the training of youth in horse riding.

A prize recognizing Kyme's leading role in Aiolis.

A reference to the local horse industry.

And others.

Dating the Coins

I am not confident in the dating of the AE coin, although auction results are consistent. Asia Minor coins have two dates associated with the three coins generally in this category. AMC #40 references both 250-200 BC and 165-140 BC. The shared obverse and reverse images with the tetradrachms make me wonder if they might be from a similar time period (165-140 BC). A more specific date is possible for the Tetradrachm: 151/150–143/142 BCE. Oakley notes that hoard evidence overwhelmingly indicates that 150-140 BCE was the period of greatest circulation of Kymean wreathed tetradrachms.

I hoped to find some overlap of my magistrate (Pythas) with other coins, but so far, no luck. I don't have a reference that offers much on these bronzes of Kyme. The two Lindgren books and my three volumes of SNG France (the wrong ones) yielded no relevant information. Lindgren 396 and BMC 68 are both not very informative (BMC on Cyme).

Oakley's die study of 540 coins has revealed twelve magistrates and 79 obverse dies, with only two die links between pairs of magistrates. Thus, the sequence of magistrates relies on style, which is admittedly not conclusive. Straton, in Oakley's proposed order, is an earlier magistrate (3rd in his proposed sequence), while Pythas from my AE coin does not appear.

Kyme in the Mid-2nd Century BCE

During the time the tetradrachm was minted, Kyme was the principal city of Aeolis in western Asia Minor, north of Smyrna. It was part of the Attalid kingdom of Pergamon, which gained control of the region after the Seleucid king’s defeat in 188 BC. Uniquely, the Attalid monarchs practiced a policy of empowering local cities. Rather than impose a strong centralized rule, they devolved considerable authority to civic governments.

Kyme flourished with a degree of autonomy, including the right to strike its own silver money, as long as it remained a loyal ally. The civic tetradrachm of Kyme bears the city’s name (KYMAIΩN) and a local magistrate’s name (ΣTPATΩN) instead of a king. Several cities in Asia Minor began issuing these distinctive “wreathed” (stephanophoric) tetradrachms around the same time. The precise motivation for this is debated. Some scholars link their appearance to the collapse of Seleucid power and the ensuing power vacuum in the 150s BC. Others suggest it was an artistic or economic trend among these cities.

A hypothesis posed by Nicholas Jones (1979) suggests that when Attalid kings imposed their “closed-currency” cistophoric coinage, an overvalued, lightweight coin meant to circulate chiefly inside Pergamene territory, neighboring autonomous cities faced a mismatch between the Attic-standard silver and the new royal currency. To keep their merchants competitive in the wider Aegean–Syrian marketplace, the poleis mobilized wealthy citizens through monetary liturgies (λειτουργία or leitourgía - literally "work for the people" or "public service") asking them to underwrite fresh, high-visibility Attic-weight “wreathed” tetradrachms.

Pergamon itself appears to have facilitated the project by supplying engravers, bullion, or political cover. The very same coins also served Attalid diplomatic aims, funding proxy warfare and cementing alliances abroad. Thus, the closed royal currency, civic benefaction, and interstate trade pressures converged. The wreathed tetradrachms emerged as a joint, ad-hoc solution that allowed local economies to preserve inter-regional exchange while the Pergamene state pursued its fiscal strategy at home.

Recent research indicates that Kyme and neighboring cities, such as Myrina and Smyrna, may have struck these coins to finance a specific conflict. They likely paid mercenary armies during the wars of the pretender Alexander Balas in the 150s BCE. Alexander Balas was vying for the Seleucid throne, and the Attalid king, a Roman ally, supported him. Large silver coins from Kyme and others would have been useful for soldiers’ wages during this tumultuous period. These coins were minted for only a brief span, perhaps a decade or two, before they were replaced by cistophoric tetradrachms.

In the broader Mediterranean, this time period saw the expansion of Rome’s influence. The Roman Republic defeated Macedon and annexed Greece by 146 BCE. Kyme’s region would soon change hands. In 133 BC, the last Attalid king bequeathed his kingdom to Rome, turning Aeolis, including Kyme, into part of Rome’s province of Asia. Thus, circa 151–142 BCE, the tetradrachms of Kyme are from the last days before Rome took over.

Ancient Jokes about Kyme

Strabo explains that the people of Kyme were not known for their brilliance. Dan Crompton’s translation of the Philogelos (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: The World’s Oldest Joke Book [2010]) includes a whole chapter on jokes about people from Kyme. Here's a sample:

154. In Kyme, an official of some sort is having a funeral. A stranger approaches those conducting the obsequies and asks, ‘Who’s the dead guy?’ One of the Kymaeans turns and points: The one lying over there on the bier.’155. A Kymaean is trying to sell a horse. Someone comes up to him and asks if the horse has thrown its first set of teeth. Two sets of teeth, actually,’ says the Kymaean. ‘How do you know that?’ ‘Well,’ comes the answer, ‘he threw mine once and my father’s once.’156. A Kymaean is selling a house. He carries around one of its building blocks to show what it’s like.157. A Kymaean is selling a horse. Asked if anything ever spooks it, he answers, ‘Upon my soul, no! He’s always all by himself in the mangerThis book reminds us that some humor hasn't changed much in 2000 years. How many Kymeans does it take to change a lightbulb?

Conclusion

The AR Tetradrachm from Kyme is not just a coin; it is a window into the past. It reflects the rich history and culture of an ancient city that played a significant role in the region. The imagery on the coin tells stories of legendary figures and civic pride. As we explore these coins, we gain insights into the lives and beliefs of those who came before us.

References

Catalogue of the Greek coins of Troas, Aeolis, and Lesbos by Wroth, Warwick, 189.

Kazmer Ujvarosy (2016), The Origin of the Story of the Amazons (Ἀμαζόνες) in the Amazesi (Ἀμάξῃσι), ‘Wagons’, or Amazoikos (Ἀμάξοίκος), ‘Wagon-Dwellers’, Etymology.

Masson, Olivier. “Quelques noms de magistrats monétaires grecs. V. Les monétaires de Kymé d'Éolide.” Revue Numismatique 6th ser., 28 (1986): 51–64.

Magee, B.R. (1996), The Amazon Myth in Western Literature. PhD Thesis, Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College.

Milne, J. G. “THE MINT OF KYME IN THE THIRD CENTURY B.C.” The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society 20, no. 79 (1940): 129–37.

Oakley, John H. "The Autonomous Wreathed Tetradrachms of Kyme, Aeolis." Museum Notes (American Numismatic Society) 27 (1982): 1–37.

Sacks, Kenneth S. “The Wreathed Coins of Aeolian Myrina.” Museum Notes (American Numismatic Society) 30 (1985): 1–43.

Sekunda, Nicholas. Review of Attalid Asia Minor: Money, International Relations, and the State, by Peter Thonemann. Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2014.05.58 (May 2014).

Steve Benner, “Ancient Greek Coins of Aiolis: Aigai, Cyme and Myrina,” CoinWeek, August 2, 2023.

2012 – R. H. J. Ashton, “Cyme in Aeolis: Persic‑Weight Didrachms, Seleucid Attic‑Weight Coinage, and Contemporary Autonomous Bronzes,” Numismatic Chronicle 172: 27‑34.

2014 – R. H. J. Ashton, “The Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Bronze Coinage of Kyme in Aiolis: A Sketch,” in Proceedings of the 1st International Congress of Anatolian Monetary History and Numismatics, Istanbul, pp. 25‑48.

2014 – B. Carroccio & M. Puglisi, “The Coins and the Relational Network of Kyme,” in Proceedings of the 1st International Congress of Anatolian Monetary History and Numismatics, Istanbul, pp. 139-156.

Jones, Nicholas F. “THE AUTONOMOUS WREATHED TETRADRACHMS OF MAGNESIA ON-MAEAND.” Museum Notes (American Numismatic Society) 24 (1979): 63–108.

These additional papers reference hoards of AR Tetradrachms, which I hoped would shed some light on magistrates, but so far not particularly relevant to my coin above.

"Commerce ('Demetrius I' hoard), 2003 (CH 10.301)", Catherine Lorber, in O. Hoover, A.R. Meadows, and U. Warterberg, eds. Coin Hoards X: Greek Hoards (New York, 2010), pp. 153-172.

"The Gaziantep Hoard", 1994 (CH 9.527; 10.308) A. R. Meadows and Arthur Houghton.

Sulla, I spotted a typo in the sentence "Strabo explains that the people of Kyme (we) not known for their brilliance:", change to (were) 😏.