A 12th Century Artuqid Mash-up

- sulla80

- Feb 7, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: May 24, 2025

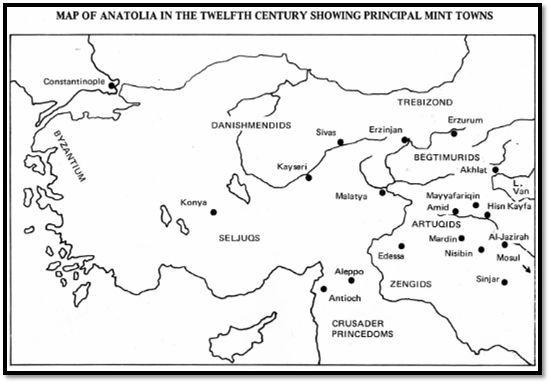

Recently I've been wandering from ancient into medieval coins and this one takes me far away from the Roman republic. When I originally stumbled across it and ultimately purchased, I was attracted to the curious and unusual mash-up of styles and symbols: Byzantine, Roman, Seleucid, Christian and Islamic. The more I collect information, the more eclectic and interesting I find this coin. A large (35mm, 15.36 grams) copper/copper-alloy Dirham of the Artuqids of Mardin, minted between 1152-1176 AD. The Artuqids of Mardin ruled in eastern Anatolia, northern Syria and northern Iraq, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries (see map).

Map Source: Eleni, Papaefthymiou. (2018). Obolos 13 Papaefthymiou. 13. 145-156.

The coin is from the founder of the "Il-Ghaziya Branch" of the Artuqids of Mardin, Najm al-Din Il-Ghazi fled Jerusalem with his brother, Sukman, in 1096/7 AD. He steadily expanded his rule from his base in Hulwan and al-Jabal, by force of personality and military might, to include the city of Mardin, Aleppo, and the territory of Mayyafariqin. The Artuquids of Mardin were the largest and longest lasting of the Turkoman kingdoms (AH 502-812 / AD 1108-1409).

The Obverse

The obverse takes its inspiration from Roman coins with facing busts such as this 3rd century AD Roman provincial coin from my collection - and perhaps bust styles of Seleucid coins.

Moesia Inferior, Marcianopolis, Macrinus with Diadumenian as Caesar, AD 217-218, Æ Pentassarion, Pontianus, consular legate

Obv: AVT K M OΠEΛ CEV MAKPEINOC K M OΠEΛ ANTΩNEINOC, confronted heads of Macrinus right, laureate, and Diadumenian, left, bareheaded

Rev: VΠ ΠONTIANOV MAPKIANOΠOΛEITΩN, Hera standing facing, head left, holding phiale and scepter; E (mark of value) to left

Ref: double die match with one described as "currently unique" by CNG as of 12-08-2015. H&J, Marcianopolis, 6.24.3.1-4 var. (E to right); AMNG I/I 722 var. (E to right); Varbanov 1185a var. (E to right).

Astrology was an important element in the Turkoman court, and this coin has Gemini illustrated on the obverse, and Virgo on the reverse. The Turkoman princes were interested in western art and culture, and the coins reflect a mixing of contemporary and classical motifs. These mashups take on new meaning as in this coin where the byzantine motif on the reverse omits the Christian cross on the globus, but retains a Virgin Mary on the reverse as figure representing the astrological sign of Virgo.

The Reverse

The reverse is a familiar scene from contemporary Byzantine coins:

The Virgin Mary, on the right, holding her hand over (or crowning) the emperor, who is standing, facing, wearing loros (a ceremonial costume of worn only by the Imperial family and senior officials), a globe between them. For example, this gold solidus of Romanus III from wildwinds:

Spengler & Sayles, in their book on Turkoman coins, link the date of this coin to AH 5549 (AD 1154) which is recorded by Ibn-al-Qalanisi as having started on the first wednesday in Muharram (18-Mar-1154) "with Gemini in the ascendant"

Islamic, Anatolia & al-Jazira (Post-Seljuk), Artuqids (Mardin), Najm al-Din Alpi, AH 547-572 / AD 1152-1176, Æ Dirham (35mm, 15.36g, 1h), Unnamed mint (Mardin[?]), undated

Obv: Diademed and draped male busts facing; Najm al-Din above and Malik Diyarbkr below; Artuqid tamgha at lower left; all in beaded cicle.

Rev: Byzantine emperor standing facing being crowned by the Virgin Mary standing facing; 3 generations of the ancestry of Najm al-Din Alpi around. The legend in cursive Naski. "abu al-Muzzafar Alpi / bin / Timurtash bin Ii-Ghazi bin / Artuq"; all in beaded circle.

Why would there be such a blend of imagery on these coins?

Monetary pragmatism: In the 1100-1200s Byzantine copper was still the small-change of the markets in eastern Anatolia. Making new copper dirhams that looked Byzantine (large flans, facing busts, double-headed eagles, etc.) signaled familiar weight, value and reliability, helping the new coins circulate and ultimately replace the old ones.

Dynastic legitimacy: Borrowing the imperial visual grammar (emperor with globus cruciger, Virgin crowning the ruler) let Turkoman princes present themselves as heirs to the Roman ecumene and to the caliph’s right to strike coins.

Multi-cultural tolerance: the population of Diyarbakr/Jazira was religiously mixed. British-Museum coins with an enthroned Christ were even counter-marked by Muslim officials, showing the imagery was officially tolerated and probably read by Christian subjects as a gesture of goodwill.

Coins from the Mardin Hoard in the British Museum Workshop ecology: Mardin’s die-engravers were often local Armenian or Syriac Christians trained on late Roman/Byzantine prototypes; with antique coins literally unearthed by builders, models were readily available so imitation was as much craft habit as ideology.

Competitive propaganda in a Crusader frontier: Showing a Muslim prince being crowned by the Virgin inverted Crusader rhetoric and advertised victory over Christian polities in a visual language the enemy understood.

References:

Lowick, N. M., Bendall, S., & Whitting, P. D. (1977). The Mardin Hoard: Islamic countermarks on Byzantine folles. A. H. Baldwin & Sons Limited.

American Numismatic Society. (n.d.). MANTIS: American Numismatic Society collection database.

Canby, S. R., Beyazit, D., Rugiadi, M., & Peacock, A. C. S. (Eds.). (2016). Court and cosmos: The great age of the Seljuqs. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

CoinCommunity Forum. (n.d.). Discussion thread: Artuqids of Mardin AE dirham [Online forum post].

Sayles, W. G. (1999). Ancient coin collecting VI: Non-classical cultures. Krause Publications.

Spengler, W. F., & Sayles, W. G. (1992). Turkoman figural bronze coins and their iconography (Vol. 1, The Artuqids). Clio’s Cabinet.

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, May 19). Artuqids. In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Wildwinds. (n.d.). Ancient coins database: Artuqids. Retrieved May 24, 2025, from https://www.wildwinds.com/

Comments